1. Make it Meaningful

1. Make it Meaningful

2. Give it a Place

3. Time Travel through Primary Sources

4. Debate over History

5. Analyze History

6. Recognize Forces that Affect History

7. Using Dates and Names Right

8. You Do Not Have to Know it All

9. You Do Have to Know HOW to DO IT

10. Presentation Resources

1. Make it Meaningful

Meaningful is More than Fun

We all love chocolate. We also all love a Thanksgiving Feast. And which of those do we appreciate more? Of course Thanksgiving is more meaningful. While chocolate is a quick fix, we are not satisfied for long. But after a good Thanksgiving meal we sit back, put up our feet and sigh. My point? Fun vs. Meaningful. Fleeting vs. Lasting.

How do we make the STUDY OF HISTORY meaningful for our students? Simply by connecting history to our natural inquisitiveness. History is a series of events. Historians try to put those events together in different ways to find reason behind the events. Answering the question of WHY.

Human minds are ever-inquisitive. We have many question words because we are not satisfied with simple answers.

Who? What? When? Where? Why? How? In What Way? For What Reason? Who Cares?

Granted, a student may not be interested initially in “What Made Rome Fall,” which is one of those critical history questions. But when you, as a teacher, turn it into a mystery and make a game of their defending their idea, suddenly you have upped-the-ante for their finding the answer.

2. Give it a Place

When we approach history, we must connect it to an existing framework. If our students do not have a framework, or have a weak one, we need to first establish that, then teach them to hang new information onto that frame.

Time periods are the clothesline, so to speak, from which we hang our newly acquired information. Because of this, one of the initial duties of the history teacher is to give context for the study of United States and World History.

The way the memory works best is when strong emotions (smells, feelings, tastes, passions) are connected with the advent of new information. Keeping this in mind, establish the framework through movies and fiction.

MOVIE NIGHT

Establishing context can be as simple as finding several historical fiction movies, setting aside two weeks of school-night movies, or a regular Friday-night movie, and conducting a sequential overview of history. These can be fictional or even well-done documentaries.

Here are the movies we’ve watched this year

- Age of Independence

Tale of Two Cities, John Adams Miniseries - US Civil War

Gone with the Wind - World War I &II

History Channel’s 2014 World Wars Miniseries I can’t recommend this enough. Very well done! - Depression

Grapes of Wrath - Post WWII

Captain America I & Agent Carter Series This has given rise to many educated discussions regarding German technology, the Nazi threat, racism, the space race, “Project Paperclip” and even the Roswell mystery.

Here’s a List of more movie ideas.

HISTORICAL FICTION & BIOGRAPHIES

Another way to give children the context they need to DO REAL HISTORY is to give them access to lots of historical fiction. If you have a Kindle, if you schedule a regular trip to the public library, or if you book-exchange with other homeschoolers, the cost for doing this goes down.

While it is important to establish the reality that “lazy writers fudge historical facts in order to make their story work,” it should not hinder your using this medium. It is more important for the student to get the general gist of the time period. Talking through the fiction vs. factual aspects is helpful. (On that note, Tale of Two Cities is one of those wrong-thesis stories. Finding out the fallacies can be part of the study of that time period.)

My novel, Trunk of Scrolls, which takes place during the Byzantine Age of Justinian, was so scrupulously researched it might actually have happened!

Here is a clearinghouse of other Historical Fiction books.

BIOGRAPHIES, on the other hand are closer to reality, though they are also often a fictional retelling of a person’s life. Teaching your students to ‘qualify’ the accuracy of what they have read (or watched) with a critical eye can prepare them for REALLY doing history.

That said, keep close track of books your student has read. Documenting the books you read is a vital aspect of creating your TRANSCRIPT PACKET. If you don’t know about THE HOMESCHOLAR yet, visit her site. Lots of great resources for you as you prepare your transcripts and get your students ready for college!

Here is the BOOK LIST form that I use. My students are required to keep a running log of books they have read. (I require Title and Author, date read, but you could ask for number of pages, or a full citation if you wish.)

NOW WHAT?

Once you have established the framework for your unit or school year, use the characters as you introduce new units. Refer back to the characters they have met and the emotions the movie or book elicited in them will connect new information to long term memory. And new information can be built onto that. Scaffolding.

For example, “Do you remember how Scarlett’s mother chased-off the overseer at the beginning of the movie? After the war, that same man returned as a ‘carpetbagger’ to try to run the O’Hara family off the farm.”

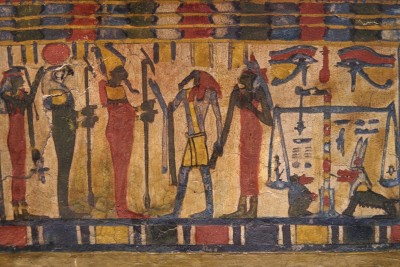

3. Time Travel through Primary Sources

The number one way to make history meaningful is to become a historian. Set up the time machine and travel back to those days. Once you have learned how to time-travel, you will be able to teach your students how to do this. The secret to time travel is primary documents–climbing into the observations of someone who lived at the time, and looking around.

My RESEARCH GUIDE with 7 SOURCES FOR PRIMARY DOCUMENTS can guide you through this process.

>> Also, take a look at OYAN’s blog where Rachel Garner writes about “Research for Historical Fiction.”<<

When a student reads a history book, they are reading a simplified compartmentalized account of regurgitated information dummied-down to fit the educational level of the intended reader. This may be necessary to provide the “framework” I mentioned above. But a teacher should not put much weight on this. It is neither fun nor meaningful. Neither is it “doing history.”

When a student reads a primary document, they are entering the mind of someone who lived many years ago. It is not easy. The student will come face-to-face with words and ideas that are confusing. (Keep a notebook for new words they meet. This will be very useful as SAT prep).

It is the process of interpreting these ideas, looking up those words, connecting the reading with their already-existing clothesline, that they will begin to find meaning. Do not expect your student to understand everything they read. The purpose of using primary source documents, explained in detail below, is to answer a different question. This is the platform we’re answering it from.

Since online searches have opened up our access to information, students need to be trained in using the internet wisely and safely.

Make sure to see 3 CRUCIAL PRINCIPLES FOR ONLINE RESEARCH

4. Debate over History

History is not names and dates. History is the reasons for things. This is why we have that famous quote of Churchill (quoting Santayana), “Those who fail to learn from history we will be doomed to repeat it.”

Doing history means presenting a debatable thesis in a persuasive manner using primary documents and reason.

What do we need to learn from history? We need to know how to look at cause and effect, how to interpret viewpoints, how to understand change, among other things. The role of the history teacher is to initiate students into the academic arena of analysis. Students are natural challengers. They enjoy questioning the status quo, they enjoy pressing their own opinions. The teacher can use this inherent part of human nature to initiate the student into analyzing history.

The best way to start this process is to use guides. I recommend three that have worked for us.

CLASSICAL HISTORIAN (Middle-school; High School)

Firstly, take a look at CLASSICAL HISTORIAN. John DeGree has a very thorough program where he shows you how to take middle school students (and high schoolers) through a “toolbox” of skills needed to be a historian, and then leading them to a series of debates as they analyze history. The debates, however, are not what you think. The purpose of these debates are for students to come to a consensus!

For example, if the prompt asks for the most significant cause for the Fall of Rome, one student may say that Weak Emperors caused the Fall, a second student may say that The Diseases caused the fall.

As the students defend their theses, they must fine-tune arguments, listen to the reasoning of other student(s) and choose the strongest most persuasive case, even if it is not their side of the debate. What matters is reasonability.

This program is best when used with two students, even at different academic levels, though if a parent is willing to do a bit of research it can be between parent and student.

CRITICAL THINKING IN UNITED STATES HISTORY SERIES (Middle-school; High School)

Secondly, I recommend Critical Thinking Company’s “Critical Thinking in United States History” series. This can be used with a single student or with a group. I wish I had discovered this sooner, since the more I use it the more I value what it offers. There are many concepts taught, and a student who goes through this series in middle school will be wonderfully prepared for high school.

While this is not a debate, per se, it approaches historical questions from differing perspectives.

PETER PAPPAS DEBATES AND iBOOKS (High School)

Thirdly, I recommend Peter Pappas’s Debates. This would be for High School level. I assign a side of each debate to one student, and following the debate plan in his introduction, have the students argue for their point. In these debates, I do not emphasize consensus as much as persuasion. The topics are opinion-driven, and I approach it as a court case. The strongest, most persuasive argument wins.

The iBooks that Peter Pappas offers look very useful. I have not used them in our class yet, having recently come across them. (They are on the schedule to start using in two weeks. I’ll update this page afterwards with my review.) I list them because of their heavy use of primary sources along with the questioning method he uses in the books. Plus they’re free.

“If men could learn from history, what lessons it might teach us!

–Samuel Taylor Coleridge

But passion and party blind our eyes, and the light which experience gives us

is a lantern on the stern which shines only on the waves behind.”

5. Analyze History

The best book I can recommend regarding teaching history is Thinking Like an Historian: Rethinking History Instruction. The book is filled with theory, which is very helpful. The classroom activities may or may not be appropriate for a homeschool teacher. But the back of the book is filled with amazing templates that help your student in analyzing the critical aspects of history. Here are the categories that need to be understood for any time or place in history are these.

Change over Time

“In what three ways did society change after…?”

Cause and Effect

“What were three most significant causes for …?” or “What were three of the worst effects of …?”

Compare and Contrast

“In what ways were…. and ….. the same? In what ways were they different?”

Define and Identify

“What is … and what are the signs of its presence during ….?”

Statement and Reaction

“What was the most far-reaching reaction to …….’s speech….? …..’s book…?”

Evaluation

“Was the …. a good or a bad change for the people during the era of ….?”

Analyzing Viewpoints

“Why were …. in favor of …. ? Why were …. against it?”

When you take any time period, or event, or individual in history approach that part of history from at least one of these analysis categories. Debate, essay, or oral report, or a combination of these, can be used for the presentation of your student’s ‘debatable historical analysis.’

6. Recognize Forces that Affect History

When we “do history” we think in categories. The first kind of category, mentioned above, is analytical method. The second kind of category is forces. You can use any of the analytical techniques above with any of the following. Since a five-paragraph/three point essay is the typical kind taught in middle and high school, choosing three of the following, or even three of one of the following is a good way to begin.

- Technology

- Social forces

- Institutional Factor

- Revolution

- Individual in History

- The role of Ideas

- Power

- International Organization

- Causation

- Loyalty

For example, when you teach your students to analyze “the three most significant causes for the Fall of Rome,” you would ask them to look at this list to find starting-point forces for those causes.

Social Forces, Individual in History, and Causation, perhaps could be three causes for the Fall.

Social forces=people identified themselves more with their people-group than with the nation as a whole. Individual in history=a series of weak emperors led to a distrust of leaders. Causation=diseases and sickness led to a diminished population which led to a weakened frontier when the barbarians arrived.

Beginning with Classical Historian or Critical Thinking Company’s series in middle school, your high schooler will be better equipped to tackle these higher order analyses.

7. Using Dates and Names Right

If your eleven year old son asks you before bed, “How can I be like MacArthur? What do I have to do to become a big general?” You know you have done something right. He knew the name, he knew to honor the man, he knew the man made a difference, and he applied it to his life.

The fact of the matter is, with the internet at our fingertips and the answer to any question we can imagine immediately available by asking “SIRI,” dates and names are only as important as the reason we need it. At what point do we need to know more?

We may need to know dates and names on the AP History exam and CLEP History exam. Yes, you may perhaps be required to match the date to event.

But even still, most of the questions are conceptual. Time-period, sociological, cause and effect, intellectual atmosphere. These make up most of the questions on the official exams and are far more important than matching date to event.

If the student has studied the era, debated over the issues, considered the individuals and their worldviews, looked for causes and forces that control events and men, they will be able to grab that information “off of their clothesline” and select the correct answer with ease. They will also be able to write the essay with fluency, even if they forget some specific date.

Dates are only as important as the changes that happened afterwards.

The dates 1066, 1492, 1776 should stir up feelings of tension and concern or excitement and dialogue. If it is an important date, it needs to be packaged with the tension of the time, and names of people who fought for their land or their ideas during that time.

Can I say this? Don’t waste your time on memorizing dates. Instead go for comprehension of ideas and the consequences of ideas. Alongside the ideas are the names of people. Some people were worldchangers, and should not be forgotten.

A really great resource for the development of ideas and the effect on history and art and culture and music is Francis Schaeffer’s How Should We Then Live. I bought the audiobook and we listen to short excerpts in the car.

8. You Do Not Have to Know it All

History is not a memorization of all that is known about all times and places since the beginning. History is interacting with the material, looking for patterns, and defining those patterns. These days, simple facts can be recalled with the touch of a tablet. But analysis that happens in the mind is a skill that will transfer to all areas of life. Critically analyzing primary source documents will prepare your student for college life and for life-choices more than almost anything else they do in school.

9. You Do Have to Know HOW to DO IT

It is not an easy task. It is fun and meaningful, but it takes a heating-up of the brain. In order to tackle questions before them, your students need to be directed. The hard work of planning those lessons is on the shoulders of the teacher.

If you prefer to take a teacher’s guide and ‘get through’ the history book, testing, questioning, moving on, that’s your choice. These methods of Critical Analysis and Doing History may seem daunting, especially if you never “did history” this way.

But this method will not only help your student. It will equip you for the future as well. When you watch the news with your students, events will strike you as relating to the forces and categories of analysis you have been learning together. When you start to look critically at events, you will find meaningfulness that supersedes the ease of simple methods.

But what is the final product? The student and teacher have grappled with history. They have developed their ability to analyze. They are ready for the challenges of college. And they have time-travelled! The end-product is worth the hard work.

10. Presentation Resources

The method of presenting post-debate historical theses is as varied as the imagination. Here are some suggestions.

I) Prezi.com

Prezi is a visually-stimulating slideshow/animation that keeps the interest of the audience. When my students use prezi, they are required to have every primary source text in red, and each slide labelled with the FORCE or the ANALYSIS CATEGORY they have used there.

II) Five paragraph/ three point essays.

You can never write too many of these. Knowing how to express yourself this way is essential for success in university.

If you do not know how to teach students how to write one of these, please see my FREE ESSAY OUTLINE, with the direction links.

A high school essay does not have to be long to be done right. The main purpose is to persuasively use facts to defend a thesis.

III) Quix Essays.

This is what I call a twenty-minute essay-write. It is great practice for the AP or SAT exams. After a sibling presents on a topic, using Prezi, I select an AP history sample essay question on a topic related to the presentation. They have to immediately analyze and formulate a thesis, and defend their idea. Sound like torture? Perhaps, but they come forth shining!–plus it’s over in 20 minutes.

IV) NaNoWriMo (or Camp Nanowrimo).

While this takes a month to do, the month of November (or April) provides a perfect opportunity to research and apply history to analysis. The role of ideas. The individual in history. Compare and contrast. Cause and effect.

The assignment could be this: Write a novel that encorporates what you have learned about the Fall of Rome, what it was like to live there and then, and what the people thought about why Rome gave way to the barbarians…. This way, the purpose for the primary-source research becomes finding props and ideas for their characters and their troubles.

V) Comic Life.

I have assigned Comiclife for a very detailed worldview analysis story, and though it is very challenging, the medium makes the task less intimidating. To be fair, it is a semester-long project on a topic that overreaches all units of the semester.

VI) Canva.

This graphic design program can be easily used to present post-debate historical conclusions. (Take a look these ideas of how to use Canva, not only in history but in all classes).

VII) YOUTUBE CHANNEL:

As this team of homeschool kids did in their BONES IN MY BACKYARD channel, you could make a Youtube Channel to post your research investigations.

[embedyt] http://www.youtube.com/embed?listType=playlist&list=PLtB_2R6ZI6x_LiGGb-CBr4U4PnyN21O6X[/embedyt]